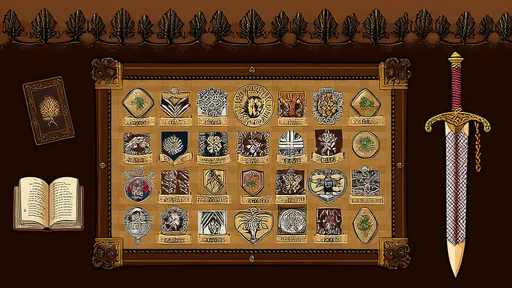

The revival of Scottish tartans has become a cultural phenomenon in recent years, with designers, historians, and clanspeople working to reclaim lost patterns and reintegrate them into modern fashion and heritage. Among the most intriguing aspects of this movement is the rediscovery of the so-called "Lost 32"—clan tartans that vanished from records due to political upheaval, industrialization, or simple neglect. These patterns, once woven into the very identity of Scottish families, are now being meticulously reconstructed from historical fragments, paintings, and oral traditions.

For centuries, tartan served as more than just fabric; it was a marker of kinship, regional identity, and social status. The suppression of Highland culture following the Jacobite rebellions, particularly after the Battle of Culloden in 1746, led to the decline of many traditional tartans. The Dress Act of 1746, which banned the wearing of tartan and other symbols of Highland identity, forced clans to abandon their distinctive patterns. Though the act was repealed in 1782, the damage was done—many tartans had already faded into obscurity.

The 19th century saw a romanticized revival of tartan, spurred by Queen Victoria’s fascination with Scotland and Sir Walter Scott’s orchestration of King George IV’s 1822 visit to Edinburgh. However, this revival was selective, prioritizing the patterns of powerful clans or those with royal connections. Smaller, less prominent clans found their tartans excluded from official registries, and over time, these designs were forgotten. The Lost 32 refers to those clan tartans that were omitted from early documentation and commercial weaving records, leaving gaps in Scotland’s textile heritage.

Today, historians and weavers are piecing together these lost patterns through a combination of detective work and creative interpretation. Fragments of old plaids preserved in museums, descriptions in centuries-old letters, and even family heirlooms with fading colors provide clues. In some cases, the tartans of allied or neighboring clans are used as references to approximate what a lost design might have looked like. The process is as much about artistry as it is about archaeology, requiring a deep understanding of natural dyes, traditional weaving techniques, and regional variations in pattern structure.

The modern tartan revival isn’t just an exercise in nostalgia; it’s a reclamation of identity. For descendants of the clans associated with the Lost 32, wearing a resurrected tartan is a powerful statement of cultural continuity. Designers, too, have embraced these once-forgotten patterns, incorporating them into high fashion and streetwear. The interplay between historical authenticity and contemporary style has given these tartans new life, ensuring they’re no longer confined to the pages of history books.

Critics argue that some reconstructed tartans are speculative at best, with no definitive proof of their original designs. Yet supporters counter that the very nature of tartan has always been fluid, adapting to changing tastes and circumstances. What matters, they say, is not an unbroken thread back to the 18th century, but the meaning imbued in these patterns today. The Lost 32, once symbols of erasure, have become emblems of resilience—a thread reconnecting Scotland’s past to its present.

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025